What causes jaw pain?

May 25, 2022 by Lisa Bywaters

Did you know the joints in your jaw are the most frequently used joints in your body? They’re constantly on the move as you talk, chew, cry, swallow, sing, smile and yawn.

Unfortunately, these joints can also be the source of pain and discomfort.

Let’s explore the anatomy of your jaw to better understand what can cause pain in these joints.

Lightly place your fingers on your face, between your nose and mouth, and spread them across your cheeks. This is the upper part of your jaw, called the maxilla. It holds your top row of teeth.

Now place your fingers on your cheeks in front of and just below your ears. This is the lower part of your jaw or the mandible. It holds your bottom row of teeth.

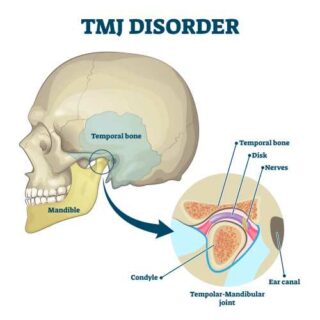

Open your mouth. You’ll feel the temporomandibular joints (TMJ) working. The rounded ends of your lower jaw (condyles) glide along the joint socket of the temporal bone. Close your mouth, and you’ll feel the condyles slide back to their original position.

The temporomandibular joints connect your lower jaw to your skull. Inside the joint, between the two bone surfaces of your skull and jaw, is a disc of cartilage. It provides a slippery cushion that helps the joints move smoothly, absorbs shocks and prevents the bones from rubbing against each other. Muscles attached to and surrounding the joints control their position and movement, and enable your jaw to move up and down, side to side, and forward and back.

Temporomandibular joint disorders (TMD) are conditions that affect the bones, joints, and muscles responsible for jaw movement. They’re the most common causes of jaw pain.

What causes temporomandibular joint disorders?

A number of different things can cause temporomandibular joint disorders, including:

- teeth grinding or clenching (known as bruxism)

- musculoskeletal conditions (e.g. fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis)

- movement or dislocation of the disc

- stress, tension, anxiety, depression

- jaw injury

- dental problems (e.g. uneven bite, ill-fitting dentures).

Who gets temporomandibular joint disorders?

TMDs are common, affecting up to 60–70% of the population, especially adults aged 20–40 years. Women are at least four times as likely to have a TMD.(1)

Many TMDs last only a short time and go away on their own. However, in some cases, they can become chronic or long-lasting.

What are the symptoms?

The most common symptom of TMDs is pain in and around the jaw, ear and temple, especially when eating. Other symptoms may include:

- clicking, popping or grinding (crepitus) when you move your jaw

- headache

- earache

- difficulty opening and closing your mouth or a ‘locking’ jaw.

How are they diagnosed?

If you’re experiencing pain in the jaw or other symptoms that are causing you problems, you should see your doctor or dentist. They’re usually able to diagnose a TMD by:

- taking your medical history – where the pain is, when it started, what makes it worse, and any other symptoms you have, and

- doing a physical examination – observing as you open and close your mouth, feeling your jaw, listening for clicking and other noises.

Sometimes they may need scans (e.g. x-rays, or CT (computed tomography scans) if the history and exam weren’t conclusive or there’s uncertainty around your diagnosis.

Treatment

Many people with a TMD find that their symptoms go away without treatment.

However, others require a treatment approach that involves a combination of self-care and medical care.

Self-care

There are simple and effective things you can do to ease the pain and other symptoms of TMDs.

- Use heat or cold packs. Cold helps reduce swelling and pain, while heat can relax your jaw muscles. Always wrap the pack in a cloth so it doesn’t touch your skin directly.

- Try some gentle stretches, exercises and massage. They help relieve muscle tension and pain in your face, jaw and neck.

- Eat soft foods, cut your food into smaller pieces and take your time eating. This will rest your temporomandibular joints and reduce the amount of work they need to do.

- Avoid eating gum, or foods that are tough or chewy, as they require lots of repetitive chewing.

- Avoid extreme jaw movements (e.g. wide yawning, yelling).

- Relax your jaw. This is something you’ll need to make a conscious effort to do because most of the time, we’re not aware that we’re clenching our jaw. It can be helpful while you’re getting in the habit of doing this to set an alarm or alert to remind you to do it.

- Do some relaxation techniques for the whole body. If you’re feeling stressed or anxious, this can aggravate your TMD. You can do many things to relax your body and mind, including going for a walk, getting a massage, listening to music, and practising mindfulness.

Medical care

Not everyone will need medical treatment to ease their symptoms. But some of the treatments used are:

- Medicines to relieve pain and inflammation and to relax muscles.

- Wearing a mouth guard while sleeping to prevent tooth grinding. Your dentist can fit you for one.

- Treating underlying conditions, such as dental problems, musculoskeletal conditions or mental health issues.

Surgery is rarely needed to treat TMDs.

Contact our free national Help Line

Call our nurses if you have questions about managing your pain, musculoskeletal condition, treatment options, mental health issues, COVID-19, telehealth, or accessing services. They’re available weekdays between 9am-5pm on 1800 263 265; email (helpline@msk.org.au) or via Messenger.

More to explore

- Temporomandibular disorders

MSD Manual Consumer Version - Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) anatomy and disc displacement animation

Alila Medical Media (video) - Temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders

Cleveland Clinic - Temporo-mandibular joint (TMJ)

The Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital - Temporomandibular joint dysfunction

healthdirect - TMD (temporomandibular disorders)

National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research - TMJ disorders

Mayo Clinic - Why do I grind my teeth and clench my jaw? And what can I do about it?

The Conversation

Reference

(1) Lomas, J. et al, 2018. Temporomandibular dysfunction. Australian Journal of General Practice, 47(4), pp.212-215.