Neck pain is a common problem many of us will experience at least once in our lives. The good news is that most cases of neck pain get better within a few days.

So what is neck pain? What causes it, and how can you manage it and get on with life?

Let’s start with a look at your spine

Let’s start with a look at your spine

It helps to know how your spine works to understand some of the potential causes of neck pain.

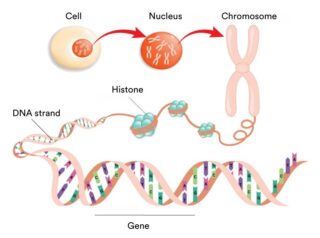

Your spine (or backbone) is made up of bones called vertebrae, stacked on top of each other to form a loose ‘S’-shaped column.

Your spinal cord transports messages to and from your brain and the rest of your body. It passes through a hole in each of the vertebrae, where it’s protected from damage. It runs through the length of your spinal column.

Each vertebra is cushioned by spongy tissue called intervertebral discs. These discs act as shock absorbers. Vertebrae are joined together by small joints (facet joints), which allow the vertebrae to slide against each other, enabling you to twist and turn. Tough, flexible bands of soft tissue (ligaments) also hold the spine in position.

Layers of muscle provide structural support and help you move. They’re joined to bone by strong tissue (tendons).

Your spine is divided into five sections: 7 cervical or neck vertebrae, 12 thoracic vertebrae, 5 lumbar vertebrae, 5 fused vertebrae in your sacrum and 4 fused vertebrae in your tailbone (or coccyx) at the base of your spine.

So what’s causing the pain?

It’s important to know that most people with neck pain don’t have any significant damage to their spine. The pain they’re experiencing often comes from the soft tissues such as muscles and ligaments.

Some common causes of neck pain are:

- muscle strain or tension – caused by things such as poor posture for long periods (e.g. hunching over while using a computer/smartphone or while reading), poor neck support while sleeping, jerking or straining your neck during exercise or work activities, anxiety and stress.

- cervical spondylosis – this arthritis of the neck is related to ageing. As you age, your intervertebral discs lose moisture and some of their cushioning effect. The space between your vertebrae becomes narrower, and your vertebrae may begin to rub together. Your body tries to repair this damage by creating bony growths (bone spurs). Most people with this condition don’t have any symptoms; however, when they do occur, the most common symptoms are neck pain and stiffness. Some people may experience other symptoms such as tingling or numbness in their arms and legs if bone spurs press against nerves. There can also be a narrowing of the spinal canal (stenosis).

- other musculoskeletal conditions such as osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, osteoporosis.

- herniated disc (also called a slipped or ruptured disc). This occurs when the tough outside layer of a disc tears or ruptures, and the soft jelly-like inside bulges out and presses on the nerves in your spine.

- whiplash – this is a form of neck sprain caused when the neck is suddenly whipped backward and then forward. This stretches the neck muscles and ligaments more than normal, causing a sprain. Whiplash most commonly occurs following a car accident and may occur days after the accident.

Symptoms

The symptoms you experience will depend on what’s causing your neck pain but may include:

- pain and/or stiffness in the neck and shoulders

- pain when moving

- difficulty turning your head

- headache.

In most cases, neck pain goes away in a few days. But if your pain doesn’t get better, or you develop other symptoms, you should see your doctor.

Or you can answer a few questions in the neck pain and stiffness symptom checker by healthdirect to find out if you need medical care. Simply click on ‘N’ and select ‘neck pain and stiffness’.

Seeing your doctor

If you need to see your doctor because of your neck pain, you can expect a discussion about potential causes or triggers of your pain, whether you’ve had neck pain before, things that make your pain worse, things that make it better. Your doctor will also conduct a thorough physical exam.

This discussion and examination by your doctor will decide whether more investigations (e.g. x-rays, CT or MRI scans) are appropriate for you. However, these tests are generally unhelpful to find a cause of the pain unless there’s an obvious injury or problem (e.g. following an accident or fall). It‘s also important to know that many investigations show ‘changes’ to your spine that represent the normal passage of time, not damage to your spine.

Often it’s not possible to find a cause for neck pain. However, it’s good to know that you can still treat it effectively without knowing the cause.

For more information about questions to ask your doctor before getting any test, treatment or procedure, visit the Choosing Wisely Australia website.

Dealing with neck pain

Most cases of neck pain will get better within a few days without you needing to see your doctor. During this time, try to keep active and carry on with your normal activities as much as possible.

The following may help relieve your symptoms and speed up your recovery:

Use heat or cold – they can help relieve pain and stiffness. Some people prefer heat (e.g. heat packs, heat rubs, warm shower, hot water bottle), others prefer cold (e.g. ice packs, a bag of frozen peas, cold gels). Always wrap them in a towel or cloth to help protect your skin from burns and tissue damage. Don’t use for longer than 10 to 15 minutes at a time, and wait for your skin temperature to return to normal before reapplying.

Rest (temporarily) and then move. When you first develop neck pain, you might find it helps to rest your neck, but don’t rest it for too long. Too much rest can stiffen your neck muscles and make your pain last longer. Try gentle exercises and stretches to loosen the muscles and ligaments as soon as possible. If in doubt, talk with your doctor.

Sleep on a low, firm pillow – too many pillows will cause your neck to bend unnaturally, and pillows that are too soft won’t provide your neck with adequate support.

Be aware of your posture – poor posture for extended periods, for example, bent over your smartphone, can cause neck pain or worsen existing pain. This puts stress on your neck muscles and makes them work harder than they need to. So whether you’re standing or sitting, make a conscious effort to be aware of your posture and adjust it if necessary, or do some gentle stretches.

Massage your pain away – massage can help you deal with your physical pain, and it also helps relieve stress and muscle tension. You can give yourself a massage, see a qualified therapist or ask a family member or friend to give you a gentle massage.

Take time to relax – try some relaxation exercises (e.g. mindfulness, visualisation, progressive muscle relaxation) to help reduce muscle tension in your neck and shoulders.

Try an anti-inflammatory or analgesic cream or gel – they may provide temporary pain relief. Talk with your doctor or pharmacist for advice.

Use medication for temporary pain relief – always follow the instructions and talk to your doctor about alternatives if you find they don’t help.

Treating ongoing neck pain

Sometimes neck pain lasts longer than a few days, and you may have ongoing neck pain. There are things you can do to manage this:

- See your doctor if the pain is worse or if you have other symptoms in addition to your neck pain such as numbness, pins and needles, fever or any difficulty with your bladder or bowel.

- See a physiotherapist or exercise physiologist – they can provide you with stretching and strengthening exercises to help relieve your neck pain and stiffness.

- Injections – some people with persistent neck pain may benefit from a long-acting steroid injection into the affected area. Talk with your doctor about whether this is right for you.

- Surgery – is rarely needed for neck pain. However, it may be required in cases where severe pain interferes with daily activities, or the spinal cord or nerves are affected.

(Originally written and published by Lisa Bywaters 2022)

Contact our free national Help Line

If you have questions about managing your pain, your musculoskeletal condition, treatment options, mental health issues, COVID-19, telehealth, or accessing services be sure to call our nurses. They’re available weekdays between 9am-5pm on 1800 263 265; email (helpline@msk.org.au) or via Messenger.

More to explore

- Neck pain

healthdirect - Neck pain

Versus Arthritis - Patient education: Neck pain (The Basics)

UpToDate - Patient education: Neck pain (Beyond the Basics)

UpToDate - Neck pain or spasms: self-care

MedlinePlus