We get asked this question a lot! But unfortunately, it’s not a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer.

Arthritis is a general term used to describe over 150 different conditions. The more accurate name for them is musculoskeletal conditions, as they affect the muscles, bones and/or joints.

They include osteoarthritis, back pain, rheumatoid arthritis, fibromyalgia, gout, polymyalgia rheumatica, lupus, osteoporosis and ankylosing spondylitis.

Around 7 million Australians live with a musculoskeletal condition, including kids. So can you avoid becoming one of them?

Maybe? Not really? It depends? 🙄

Because there are many different types of musculoskeletal conditions, the answer depends on various factors.

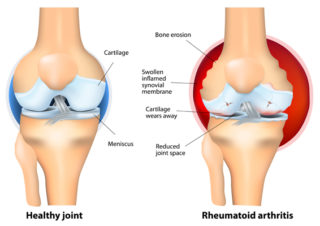

For conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and lupus, we don’t really know their cause. Without knowing the cause, it’s hard to prevent something from occurring.

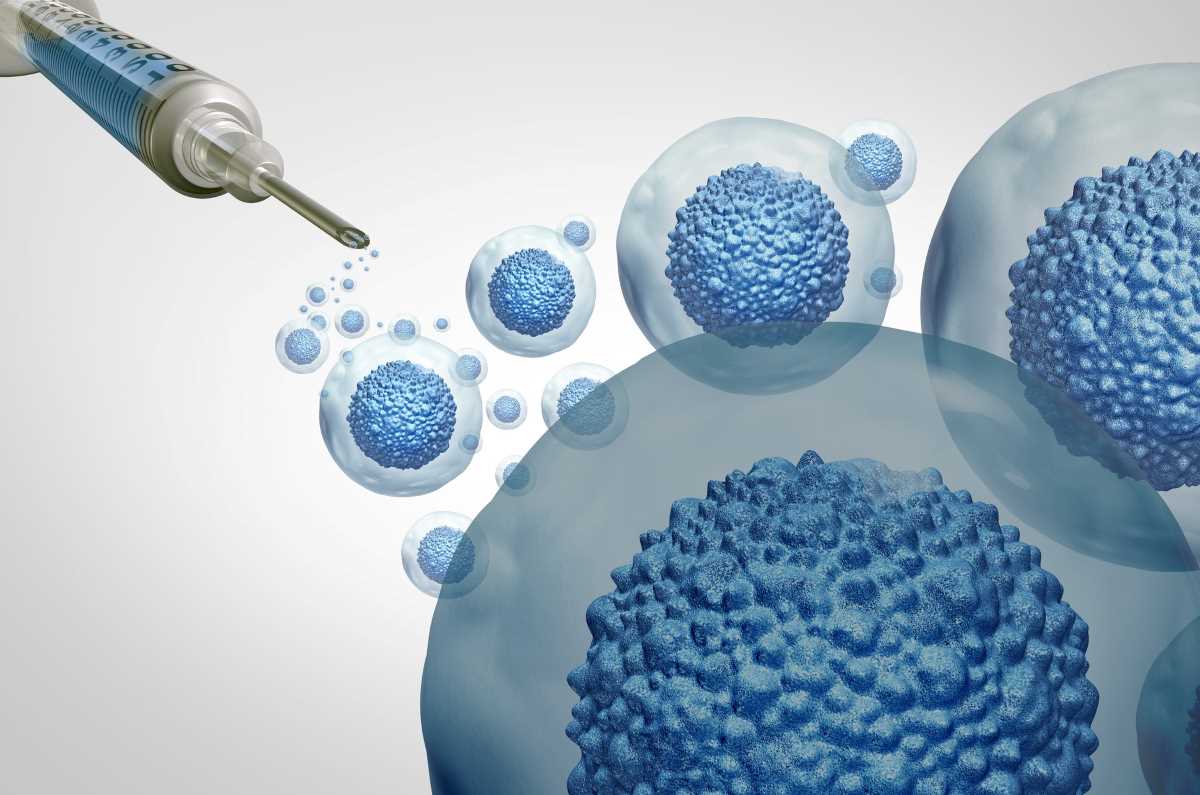

What we do know is that they’re autoimmune conditions. That means they occur due to a malfunctioning immune system. Instead of attacking germs and other foreign bodies, the immune system targets joints and healthy tissue, causing ongoing inflammation and pain. We don’t know why this happens, but scientists believe that a complex mix of genes and environmental factors is involved.

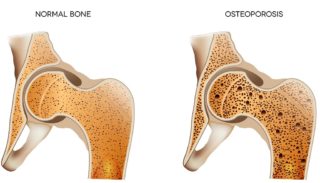

At this stage, we can’t change a person’s genetics to prevent them from developing an autoimmune type of arthritis, or conditions like osteoporosis and Paget’s disease, which are also linked to genetics. Many musculoskeletal conditions also become more common as you get older and are more common in women.

Other health issues, such as diabetes, kidney disease, coeliac disease, and even other musculoskeletal conditions 😫, can also increase your risk of developing a musculoskeletal condition. For example, chronic kidney disease can increase your chance of developing gout, and rheumatoid arthritis increases your risk of developing osteoporosis and fibromyalgia.

So that’s the bad news.

The good news is there are things you can do to reduce your risk of developing a musculoskeletal condition. Or, if you develop one, reduce its impact and severity.

Maintain a healthy weight

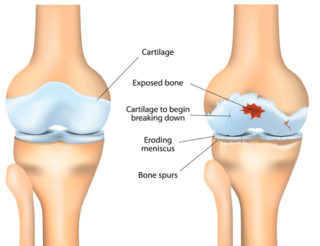

Excess body weight puts more pressure on your joints and increases the stress on cartilage, especially in weight-bearing joints like your hips, knees, and back. For every kilo of excess weight you carry, an additional load of 4kgs is put on your knee joints.

In addition to putting added stress on joints, fat releases molecules that increase inflammation throughout your body, including your joints. Being at a healthy weight reduces this risk.

Being overweight or obese is strongly linked to developing osteoarthritis (OA), most often in the knees. Hand OA is also more common in people who are overweight.

Back pain and inflammatory conditions such as gout, rheumatoid arthritis, and psoriatic arthritis have also been linked to being overweight.

If you have a musculoskeletal condition, maintaining a healthy weight, or losing weight if you’re overweight, can decrease your pain, allow you to become more active, and decrease your risk of developing other health problems like heart disease and diabetes.

Quit smoking

As well as the obvious links to cancer and lung disease, smoking’s linked to back pain, neck pain, rheumatoid arthritis and osteoporosis. Smoking also causes fatigue and slower healing, which can make pain worse. And it can make some medications less effective.

So quitting smoking has many health benefits. Within weeks of quitting, you’ll breathe easier and have more energy, making it easier to exercise and do your day-to-day activities. Find out more about the impact of smoking and ways to quit for good.

Stay active and exercise regularly

Regular exercise is vital for overall good health and keeps you fit, independent and mobile. Being active helps keep your muscles, bones and joints strong so that you can keep moving. It reduces your risk of developing other conditions such as osteoporosis, heart disease, diabetes and some forms of cancer. It boosts your mood, benefits your mental health, helps with weight control and improves sleep.

Having strong muscles is also essential to reduce your risk of falls.

Look after your mental health

Mental health conditions can increase the likelihood of developing some musculoskeletal conditions. For example, people with depression are at greater risk of developing chronic back pain. And living with a painful musculoskeletal condition can have a significant impact on mental health.

If you’re living with anxiety, depression, or another mental health condition and feel that you’re not coping well, it’s important to seek help as soon as possible. This will ensure you don’t prolong your illness and worsen your symptoms. It becomes harder and harder to climb out of a depressive episode the longer you wait. Similarly, the longer you put off seeking help for anxiety, the more anxious you may become about taking that first step.

There are many different types of treatment options available for mental health conditions. The important thing is to find the right treatment and health professional that works for you. With the proper treatment and support, they can be managed effectively.

Get enough calcium and vitamin D

Calcium and vitamin D are essential to building strong, dense bones when you’re young and keeping them strong and healthy as you age.

Getting enough calcium each day will reduce your risk of bone loss, low bone density, and osteoporosis.

Calcium is found in many foods, including dairy foods, sardines and salmon, almonds, tofu, baked beans, and green leafy vegetables.

Vitamin D is also essential for strong bones, muscles and overall health. The sun is the best natural source of vitamin D, but it can be found in some foods.

If you’re unable to get enough calcium or vitamin D through your diet or safe sun exposure, talk about calcium and/or vitamin D supplements with your doctor.

Protect your joints

Joint injuries increase your risk of getting OA. People who’ve injured a joint, perhaps while playing a sport, are more likely to eventually develop arthritis in that joint. So it’s important to protect against injury by:

- maintaining good muscle strength

- warming up and cooling down whenever you exercise or play sport

- using larger, stronger joints or parts of the body for activities, for example, carrying heavy shopping bags on your forearms, rather than the small joints in your fingers

- using proper technique when exercising, for example, when using weights at the gym or when playing sports, especially those that involve repetitive motions such as tennis or golf

- maintaining a healthy weight

- avoiding staying in one position for extended periods

- seeking medical care quickly if you injure a joint.

Drink alcohol in moderation

Excessive alcohol consumption contributes to bone loss and weakened bones, increasing your risk of osteoporosis. For people with gout, drinking too much alcohol, especially beer, can increase your risk of a painful attack.

It can also affect your sleep, interact with medicines, and affect your mental health. To find out more about the risks of drinking too much alcohol and how you can reduce your alcohol intake, read ‘Should I take a break from booze?’.

Manage stress

While stress on its own is unlikely to cause someone to develop a musculoskeletal condition, chronic stress or a stressful event may be a contributing factor, especially with conditions such as fibromyalgia and back pain.

It can also cause issues with sleep, mood, increase pain, and make you more prone to flares if you have a musculoskeletal condition. It can then become a cycle of stress, poor sleep, pain and more stress. And this can be a difficult cycle to break.

But there are things you can do to deal with stress. Try relaxation techniques such as meditation, breathing exercises and visualisation, and avoid caffeine, alcohol and cigarettes.

Talk to someone – whether it’s a family member, friend or mental health professional, about what’s stressing you out so you can deal with it.

Talk with your doctor

If you’ve been experiencing joint or muscle pain, it’s important that you discuss your symptoms with your doctor. Getting a diagnosis as soon as possible means that treatment can start quickly, reducing the risk of joint damage and other complications.

Final word

While at this moment in time, we can’t absolutely 100% prevent ourselves from getting a musculoskeletal condition, the good news is that early diagnosis and treatment will give you the best outcomes.

Treatments for many of these conditions have come a long way in recent years, and most people live busy, active lives with musculoskeletal conditions. 😊

More to explore